Asylum – a place of refuge or a house of horror?

Asylum is a word we hear often. Thousands of refugees escaping from peril in their homelands make the hazardous journey to new countries in search of a better safer life. The word literally means ‘a place of refuge’ but that was not how it was always perceived in historical terms – an asylum was indeed a place, but few passed through its doors voluntarily.

There have always been social stigmas attached to mental health disorders. From the beginning of time, individuals considered to be different were either seen as figures of fun or were feared because of their unusual or occasionally violent behaviour. The majority of causes of ‘insanity’ as it was referred to were misunderstood and were therefore untreatable. Up until the mid-nineteenth century many people, including the king, were locked away and the attitude of ‘out of sight, out of mind’ was adopted.

Stigmas always equal shame…

Changes in public perception, improved medical understanding and enhanced legislation helped improve the lives of those who suffered from a multitude of disorders. New asylums were built – most counties had one and some had three or four – and early psychiatrists, ‘alienists or mad doctors’ as they were called began to understand and cure a variety of conditions. But the social stigma of entering the doors of the asylum remained – the shame existed and still exists in many families – and ‘mad Aunty Minnie’ was forgotten about and written out of the family’s history. It was not something that could be embraced with pride.

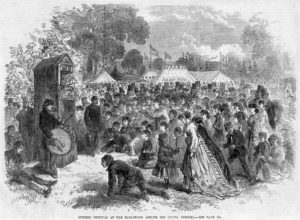

However, contrary to popular belief, life in an asylum was not completely disastrous for those locked away behind closed doors. The new asylums of the nineteenth century were built as self-contained estates which resembled stately homes. They were positioned on the outskirts of towns with good rail links and a plentiful supply of fresh water. Patient accommodation was south facing to maximise the benefits of sunshine and they were encouraged to work to take their mind off their problems – it was a system called ‘moral therapy’. There were indoor bathrooms, hot running water, three meals a day, access to reading material and most had their own churches. Dances, picnics and sporting activities were available – it was a far cry from the treatment of the insane the previous century.

Did social class determine your level of privacy?

However the negative side was never far away. Shared dormitories, no privacy, few visitors and the ability to sign yourself out was not an option. Public asylums were filled with an assortment of people from all walks of life and the only segregation was between the sexes. There was no ‘middle class’ option – people were either admitted as pauper or private patients – an expense few could afford even if their families were in paid employment.

On Monday 23 June 1873, the Birmingham Daily Post published an account of Mrs Alice Hadfield Petschler’s time spent in Parkside Asylum in Macclesfield, Cheshire. Alice was the young widow of a well-known Manchester photographer whose relatives were people of means and position – her brother-in-law was a doctor. She had four children but claimed to have been forcibly removed from her family on the pretense of going for a drive. Her destination was not specified but she arrived at the asylum in November 1871 and was diagnosed with ‘religious mania’. After her release ten months later, she wrote a long letter of complaint and recounted some of the horrors she had been subjected to:

‘The nurses treated me as a pauper and used force to me when I refused to submit, telling me I was only a pauper like the rest’.

The details of her treatment caused such a wide sensation that the Committee of Visiting Magistrates of the Asylum immediately conducted an enquiry. Despite their investigation, the Commissioners were unable to corroborate many of her accusations. They summed up by declaring that:

‘Mrs Petschler does not appear at any time to have realised the fact that she was insane and required care in an asylum; but she seems to have been mainly and principally aggrieved at having been sent to a pauper asylum, and at having to associate with patients beneath herself in station and education’.

A great sensation brought about a revelation

Many individuals were grateful for the refuge and care provided by the asylum. Esther Gosling from Stockport asked to be admitted. She was epileptic, a condition she believed she had caught from her sister Violet because they shared a bedroom. Unable to look after herself or work she hoped the asylum doctors would cure her. Epilepsy in nineteenth-century Britain remained misunderstood and was considered incurable. Both Esther and her sister Violet died from the condition in their mid-twenties having received no medical treatment as none was available.

Medicine has advanced and the old asylum system has disappeared and been replaced with care in the community and integration. Many of the original nineteenth century asylum buildings still exist. Some have been incorporated into local hospitals but others have been developed into luxury residential accommodation and therefore remain a refuge for whoever lives in them.

Written by Kathryn Burtinshaw

Liked this article? Our next blog B for Bastardisation is sure to capture your interests!