Gone but not forgotten

In the First World War over one million British and Empire soldiers, sailors and airmen died and went missing in action (M.I.A). Men would fight and die in their anonymous thousands in the mud of Flanders, the Somme and elsewhere throughout the many fields of conflict. Many of their bodies were never identified or even recovered.

‘Present and correct’ at the start of battle, they were ominously absent from the final muster – and were therefore ‘missing-in-action’. Dog-tags (identity tags), regimental badges and other effects helped to identify some of the bodies who would be recorded as killed-in-action (K-i-A). Early simple dog-tags were worn round the necks of soldiers but a new reformed system was instituted by Fabian Ware, a politician and veteran of the Second Boer War, and the founder of the Imperial War Graves Commission (later to become the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CGWC)). Every soldier now wore two dog-tags made of pressed fibre – one red fireproof and the other a green waterproof one. The tags were strung in a particular way – the red tag was easily cut off but the green tag would be left with the body. When the red tag was sent to the adjutant of the regiment it confirmed a killed-in-action death and the next-of-kin would be informed.

Many recorded as ‘missing-in-action’ were never be found. They might have been wounded, captured or a few shell-shocked individuals may have even deserted in terror or suffering from shell-shock (risking being ‘shot at dawn’ by their fellow colleagues for cowardice). However, many were blown to bits, or their bodies decomposed and perished in the rat-infested trenches. They became unidentifiable and bore no resemblance to the smart young men who had gone to war. After a period of time the ‘missing-in-action’ became ‘missing presumed dead’. The names of the missing were known to the authorities but the huge list of names could never be matched to the thousands of unidentified corpses of these victims of war. Throughout the war graveyards of France and Flanders, Turkey, Palestine, Iraq, and elsewhere are thousands of CWGC headstones labelled simply ‘a soldier of the Great War’ without a name.

The Ypres Gate Memorial in Belgium records the names of over 54 thousand soldiers who died before 16 August 1917 and have no known grave. The recently restored Thiepval Memorial in France commemorates more than 72 thousand men of British and South African forces who died in the Somme before March 1918 who have no known grave. The Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing’ records over 33 thousand UK forces and over 1,150 New Zealanders, including three Victoria Cross winners, who fell in either the Battle of Broodseinde or the First battle of Passendaele in October 1917 “whose graves are only known unto God”.

However, some of the First World War missing have been found in recent years thanks to DNA technology. In 2009 the bodies of 250 Australian and British soldiers, buried by the Germans in 1916, were exhumed from the military cemetery at Fromelles in the north of France. Of these, 159 Australian soldiers have so far been identified, enabling the CWGC to erect a new headstone for each of them bearing their name, and bringing closure to their families.

Of course, it did not end there: many went missing in subsequent conflicts.

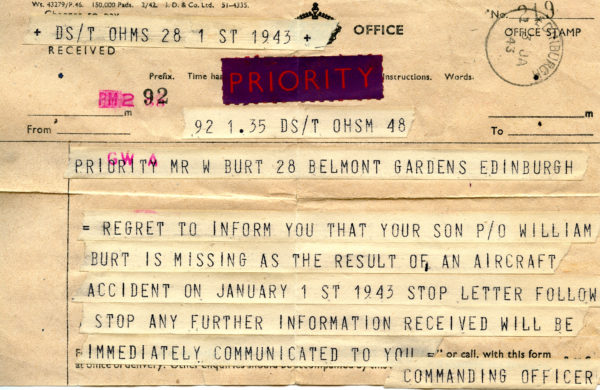

On 3 January 1943 my grandparents received this telegram:

Written by John Burt

N is for News in the next blog for the Blogging from A-Z April Challenge. You can read the blog here.